3.4 The Addition Rule for Probability

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, you should be able to:

- Identify mutually exclusive events.

- Apply the Addition Rule to compute probability.

- Use the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle to compute probability.

Up to this point, we have looked at the probabilities of simple events. Simple events are those with a single, simple characterization. Sometimes, though, we want to investigate more complicated situations. For example, if we are choosing a college student at random, we might want to find the probability that the chosen student is a varsity athlete or in a Greek organization. This is a compound event: there are two possible criteria that might be met. We might instead try to identify the probability that the chosen student is both a varsity athlete and in a Greek organization. In this section and the next, we’ll cover probabilities of two types of compound events: those build using “or” and those built using “and.” We’ll deal with the former first.

Mutual Exclusive Events

Before we get to the key techniques of this section, we must first introduce some new terminology. Let’s say you’re drawing a card from a standard deck. We’ll consider 3 events: ![]() is the event “the card is a ♡,”

is the event “the card is a ♡,” ![]() is the event “the card is a 10,” and

is the event “the card is a 10,” and ![]() is the event “the card is a ♠.” If the card drawn is J♠, then

is the event “the card is a ♠.” If the card drawn is J♠, then ![]() and

and ![]() didn’t occur, but

didn’t occur, but ![]() did. If the card drawn is instead 10♠, then

did. If the card drawn is instead 10♠, then ![]() didn’t occur, but both

didn’t occur, but both ![]() and

and ![]() did.

did.

We can see from these examples that, if we are interested in several possible events, more than one of them can occur simultaneously (both ![]() and

and ![]() , for example). But, if you think about all the possible outcomes, you can see that

, for example). But, if you think about all the possible outcomes, you can see that ![]() and

and ![]() can never occur simultaneously; there are no cards in the deck that are both ♡ and ♠. Pairs of events that cannot both occur simultaneously are called mutually exclusive events. Let’s go through an example to help us better understand this concept.

can never occur simultaneously; there are no cards in the deck that are both ♡ and ♠. Pairs of events that cannot both occur simultaneously are called mutually exclusive events. Let’s go through an example to help us better understand this concept.

EXAMPLE 1

Decide whether the following events are mutually exclusive. If they are not mutually exclusive, identify an outcome that would result in both events occurring.

- You are about to roll a standard 6-sided die.

is the event “the die shows an even number” and

is the event “the die shows an even number” and  is the event “the die shows an odd number.”

is the event “the die shows an odd number.” - You are about to roll a standard 6-sided die.

is the event “the die shows an even number” and

is the event “the die shows an even number” and  is the event “the die shows a number less than 4.”

is the event “the die shows a number less than 4.” - You are about to flip a coin 4 times.

is the event “at least 2 heads are flipped” and

is the event “at least 2 heads are flipped” and  is the event “fewer than 3 tails are flipped.”

is the event “fewer than 3 tails are flipped.”

Show/Hide Solution

- Let’s look at the outcomes for each event:

and

and  . There are no outcomes in common, so

. There are no outcomes in common, so  and

and  are mutually exclusive.

are mutually exclusive. - Again, consider the outcomes in each event:

and

and  . Since the outcome 2 belongs to both events, these are not mutually exclusive.

. Since the outcome 2 belongs to both events, these are not mutually exclusive. - Suppose the results of the 4 flips are HTTH. Then at least 2 heads are flipped, and fewer than 3 tails are flipped. That means that both

and

and  occurred, and so these events are not mutually exclusive.

occurred, and so these events are not mutually exclusive.

TRY IT 1

Suppose you’re about to draw one card from a deck containing only these 10 cards: A♡, A♠, A♣, A♢, K♠, K♣, Q♡, Q♠, J♡, J♠. Decide whether these events are mutually exclusive:

is the event “the card is an ace” and

is the event “the card is an ace” and  is the event “the card is a king.”

is the event “the card is a king.” is the event “the card is a ♡” and

is the event “the card is a ♡” and  is the event “the card is an ace.”

is the event “the card is an ace.” is the event “the card is a ♡” and

is the event “the card is a ♡” and  is the event “the card is a king.”

is the event “the card is a king.”

Show Solution

1. ![]() = {A hearts, A spades, A clubs, A diamonds}

= {A hearts, A spades, A clubs, A diamonds}![]() = {K hearts, K spades, K clubs, K diamonds}

= {K hearts, K spades, K clubs, K diamonds}

There are no outcomes in common.

These are mutually exclusive.

2. They have the Ace of hearts in common.

They are not mutually exclusive.

3. Mutually exclusive

The Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events

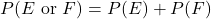

If two events are mutually exclusive, then we can use addition to find the probability that one or the other event occurs.

If ![]() and

and ![]() are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then

![]() .

.

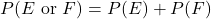

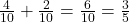

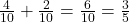

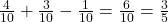

Why does this formula work? Let’s consider a basic example. Suppose we’re about to draw a Scrabble tile from a bag containing A, A, B, E, E, E, R, S, S, U. What is the probability of drawing an E or an S? Since 3 of the tiles are marked with E and 2 are marked with S, there are 5 tiles that satisfy the criteria. There are ten tiles in the bag, so the probability is ![]() . Notice that the probability of drawing an E is

. Notice that the probability of drawing an E is ![]() and the probability of drawing an S is

and the probability of drawing an S is ![]() ; adding those together, we get

; adding those together, we get ![]() . Look at the numerators in the fractions involved in the sum: the 3 represents the number of E tiles and the 2 is the number of S tiles. This is why the Addition Rule works: The total number of outcomes in one event or the other is the sum of the numbers of outcomes in each of the individual events.

. Look at the numerators in the fractions involved in the sum: the 3 represents the number of E tiles and the 2 is the number of S tiles. This is why the Addition Rule works: The total number of outcomes in one event or the other is the sum of the numbers of outcomes in each of the individual events.

EXAMPLE 2

For each of the given pairs of events, decide if the Addition Rule applies. If it does, use the Addition Rule to find the probability that one or the other occurs.

- You are rolling a standard 6-sided die. Event

is “roll an even number” and event

is “roll an even number” and event  is “roll a 3.”

is “roll a 3.” - You are drawing a card at random from a standard 52-card deck. Event

is “draw a ♡” and event

is “draw a ♡” and event  is “draw a king.”

is “draw a king.” - You are rolling a pair of standard 6-sided dice. Event

is “roll an odd sum” and event

is “roll an odd sum” and event  is “roll a sum of 10.”

is “roll a sum of 10.”

Show/Hide Solution

- Since 3 is not an even number, these events are mutually exclusive. So, we can use the Addition Rule: since

and

and  , we get

, we get  .

. - If the card drawn is K♡, then both

and

and  occur. So, they aren’t mutually exclusive, and the Addition Rule doesn’t apply.

occur. So, they aren’t mutually exclusive, and the Addition Rule doesn’t apply. - Since 10 is not odd, these events are mutually exclusive. Since

and

and  , the Addition Rule gives us

, the Addition Rule gives us  .

.

TRY IT 2

Suppose you’re about to draw one card from a deck containing only these 10 cards: A♡, A♠, A♣, A♢, K♠, K♣, Q♡, Q♠, J♡, J♠. If appropriate, use the Addition Rule to find the probability that one or the other of these events occurs:

is the event “the card is an ace” and

is the event “the card is an ace” and  is the event “the card is a king.”

is the event “the card is a king.” is the event “the card is a ♡” and

is the event “the card is a ♡” and  is the event “the card is an ace.”

is the event “the card is an ace.” is the event “the card is a ♡” and

is the event “the card is a ♡” and  is the event “the card is a king.”

is the event “the card is a king.”

Show Solution

1. Sample Space:

| A heart | A spade | A club | A diamond | K spade | K club | Q heart | Q spade | J heart | J spade |

There are 10 cards, 4 of which are Aces and 2 are kings.

The Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If ![]() and

and ![]() are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then ![]() .

.

P(Ace or King) = ![]() .

.

2. Not appropriate; the events are not mutually exclusive.

Sample Space:

| A heart | A spade | A club | A diamond | K spade | K club | Q heart | Q spade | J heart | J spade |

There are 10 cards.

These are not mutually exclusive events. There is only one card that is both a heart and an Ace, and that is the Ace of hearts. It is not appropriate to use the Addition Rule, so we do not continue this exercise.

3. Sample Space:

| A heart | A spade | A club | A diamond | K spade | K club | Q heart | Q spade | J heart | J spade |

There are 10 cards, three of which are hearts and two of which are kings.

(Note, the kings are a spade and a club.)

The Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If ![]() and

and ![]() are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then ![]() .

.

P(heart or king) = ![]() .

.

Finding Probabilities When Events Aren’t Mutually Exclusive

Let’s return to the example we used to explore the Addition Rule: We’re about to draw a Scrabble tile from a bag containing A, A, B, E, E, E, R, S, S, U. Consider these events: ![]() is “draw a vowel” and

is “draw a vowel” and ![]() is “draw a letter that comes after L in the alphabet.” Since there are 6 vowels,

is “draw a letter that comes after L in the alphabet.” Since there are 6 vowels, ![]() . There are 4 tiles with letters that come after L alphabetically, so

. There are 4 tiles with letters that come after L alphabetically, so ![]() . What is

. What is ![]() ? If we blindly apply the Addition Rule, we get

? If we blindly apply the Addition Rule, we get ![]() , which would mean that the compound event

, which would mean that the compound event ![]() or

or ![]() is certain. However, it’s possible to draw a B, in which case neither

is certain. However, it’s possible to draw a B, in which case neither ![]() nor

nor ![]() happens. Where’s the error?

happens. Where’s the error?

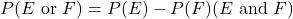

The events are not mutually exclusive: the outcome U belongs to both events, and so the Addition Rule doesn’t apply. However, there’s a way to extend the Addition Rule to allow us to find this probability anyway; it’s called the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle. In this example, if we just add the two probabilities together, the outcome U is included in the sum twice: It’s one of the 6 outcomes represented in the numerator of ![]() , and it’s one of the 4 outcomes represented in the numerator of

, and it’s one of the 4 outcomes represented in the numerator of ![]() . So, that particular outcome has been “double counted.” Since it has been included twice, we can get a true accounting by excluding it once:

. So, that particular outcome has been “double counted.” Since it has been included twice, we can get a true accounting by excluding it once: ![]() . We can generalize this idea to a formula that we can apply to find the probability of any compound event built using “or.”

. We can generalize this idea to a formula that we can apply to find the probability of any compound event built using “or.”

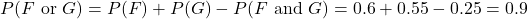

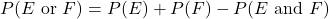

Inclusion/Exclusion Principle: If ![]() and

and ![]() are events that contain outcomes of a single experiment, then

are events that contain outcomes of a single experiment, then

![]() .

.

It’s worth noting that this formula is truly an extension of the Addition Rule. Remember that the Addition Rule requires that the events ![]() and

and ![]() are mutually exclusive. In that case, the compound event

are mutually exclusive. In that case, the compound event ![]() is impossible, and so

is impossible, and so ![]() . So, in cases where the events in question are mutually exclusive, the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle reduces to the Addition Rule.

. So, in cases where the events in question are mutually exclusive, the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle reduces to the Addition Rule.

EXAMPLE 3

Suppose we have events ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , associated with these probabilities:

, associated with these probabilities:

Compute the following:

Show/Hide Solution

- Using the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle:

- Again, we’ll apply the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle:

- Applying the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle one more time:

TRY IT 3

You are about to roll a special 6-sided die that has both a colored letter and a colored number on each face. The faces are labeled with: a red 1 and a blue A, a red 1 and a green A, an orange 1 and a green B, an orange 2 and a red C, a purple 3 and a brown D, an orange 4 and a blue E. Find the probabilities of these events:

- The number is orange or even.

- The letter is green or an A.

- The number is even, or the letter is green.

Show Solution

1. Sample Space:

| Letter side | Red 1 | Red 1 | Orange 1 | Orange 2 | Purple 3 | Orange 4 |

| Number side | Blue A | Green A | Green B | Red C | Brown D | Blue E |

Orange: Orange 1, Orange 2. This is 2 outcomes.

Even: Orange 2, Orange 4. This is 2 outcomes.

Outcomes in common: Orange 2. This is 1 outcome in common.

You can use the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle. If ![]() and

and ![]() are not mutually exclusive, then

are not mutually exclusive, then

![]() .

.

P(orange or even) = P(orange) + P(even) – P(orange and even) = ![]() .

.

2. Sample Space:

| Letter side | Red 1 | Red 1 | Orange 1 | Orange 2 | Purple 3 | Orange 4 |

| Number side | Blue A | Green A | Green B | Red C | Brown D | Blue E |

Green: Green A, Green B. This is 2 outcomes.

A: Blue A, Green A. This is 2 outcomes.

Common: Green A. This is 1 outcome in common.

They are not mutually exclusive.

You can use the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle. If ![]() and

and ![]() are not mutually exclusive, then

are not mutually exclusive, then

![]() .

.

P(green or A) = P(green) + P(A) – P(green and A) = ![]() .

.

3. Sample Space:

| Letter side | Red 1 | Red 1 | Orange 1 | Orange 2 | Purple 3 | Orange 4 |

| Number side | Blue A | Green A | Green B | Red C | Brown D | Blue E |

Even: Orange 2, Orange 4, which makes 2 outcomes.

Green: Green A, Green B, which makes 2 outcomes.

They are mutually exclusive.

You can use the Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If ![]() and

and ![]() are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then ![]() .

.

P(even or green) = ![]() .

.

Check Your Understanding

You are about to draw a card at random from a deck containing only these 10 cards: A♡, A♠, A♣, A♢, K♠, K♣, Q♡, Q♠, J♡, J♠. Compute the following probabilities:

- You draw an ace or a king.

- You draw a ♠ or a ♣.

- You draw an ace or a ♡.

- You draw a jack or a ♡.

- You draw a jack or a ♣.

- You draw a king or a ♢.

Check your understanding answers

- Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade These are mutually exclusive.

There are 10 cards.

You can use the Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If

and

and  are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then  .

.There are 4 Aces and 2 kings.

P(A or K) =

.

. - Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade These are mutually exclusive.

There are 10 cards.

You can use the Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If

and

and  are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then  .

.There are 4 spades and 2 clubs.

P(spade or club) =

.

. - Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade Ace or heart are not mutually exclusive.

Aces: A heart, A spade, A club, A diamond.

Hearts: Q heart, J heart.

In common: Ace of hearts.

There are not mutually exclusive events.

There are 10 cards.

You can use the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle. If

and

and  are not mutually exclusive, then

are not mutually exclusive, then .

.P(Ace or heart) = P(A) + P(heart) – P(A and heart) =

.

. - Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade Jacks: Jack heart, Jack spade.

Hearts: Ace hearts, Queen hearts, Jack hearts.

Jack and Heart: J heart.

These are not mutually exclusive.

There are 10 cards.

You can use the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle. If

and

and  are not mutually exclusive, then

are not mutually exclusive, then .

.P(Jack or heart) = P(J) + P(heart) – P(J and heart) =

.

. - Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade Jacks: Jack heart, Jack spade.

Clubs: Ace club, King club.

These are mutually exclusive.

There are 10 cards.

If

and

and  are not mutually exclusive events, then

are not mutually exclusive events, then  .

.P(jack or club) =

.

. - Sample Space:

A heart A spade A club A diamond K spade K club Q heart Q spade J heart J spade Kings: King spade, King club.

Diamonds: Ace diamond.

These are mutually exclusive.

There are 10 cards.

You can use the Addition Rule for Mutually Exclusive Events:

If

and

and  are mutually exclusive events, then

are mutually exclusive events, then  .

.P(King or diamond) =

.

.

3.5 Exercise Set

For the following exercises, we are considering a special 6-sided die, with faces that are labeled with a number and a letter: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2C, 4A, and 4E. You are about to roll this die once.

- What is the probability of rolling a 1 or a 2?

- What is the probability of rolling a 4 or a B?

- What is the probability of rolling an even number or a consonant?

- What is the probability of rolling a 2 or an E?

- What is the probability of rolling an odd number or a vowel?

- What is the probability of rolling an odd number or a consonant?In the following exercises, you are drawing a single card from a standard 52-card deck.

- What is the probability that you draw a ♡ or a ♠?

- What is the probability that you draw a ♡ or a 5?

- What is the probability that you draw a 2 or a 3?

- What is the probability that you draw a card with an even number on it?

- What is the probability that you draw a card with an even number on it or a ♣?

- What is the probability that you draw an ace or a king?

- What is the probability that you draw a face card (king, queen, or jack)?

- What is the probability that you draw a face card or a ♣?For the following exercises, use the table provided here, which breaks down the enrollment at a certain liberal arts college by class year and area of study:

Class Year First-Year Sophomore Junior Senior Totals Area Of Study Arts 138 121 148 132 539 Humanities 258 301 275 283 1117 Social Science 142 151 130 132 555 Natural Science/Mathematics 175 197 203 188 763 Totals 713 770 756 735 2974 - What is the probability that a randomly selected student is a first-year or sophomore?

- What is the probability that a randomly selected student is a junior or an arts major?

- What is the probability that a randomly selected student is majoring in the social sciences or the natural sciences/mathematics?

- What is the probability that a randomly selected student is a social science major or a sophomore?

- What is the probability that a randomly selected student is a senior or is a humanities major?

- What is the probability that a randomly selected student is majoring in the arts or humanities?

The following exercises are about the casino game roulette. In this game, the dealer spins a marble around a wheel that contains 38 pockets that the marble can fall into. Each pocket has a number (each whole number from 0 to 36, along with a double zero) and a color (0 and 00 are both green; the other 36 numbers are evenly divided between black and red). Players make bets on which number (or groups of numbers) they think the marble will land on.

What is the probability of winning at least one of the following pairs of bets on a single spin of the wheel?

- First dozen (wins if any of the numbers 1–12 come up) or second dozen (wins on 13–24)

- Red (wins on any of the 18 red numbers) or black (wins on any of the 18 black numbers)

- Even (wins on any even number 2–36; 0 and 00 both lose this bet) or red

- Middle column (the numbers 2, 5, 8, 11, …, 35) or black

- Middle column or red

- Right column (the numbers 3, 6, 9, …, 36) or black

- Right column or red

- Odd or black

- Even or black

- The street bet (a bet on 3 numbers that make up a row on the table) on 1, 2, 3 or odd

- The street bet on 1, 2, 3 or even

- The corner bet (a bet on 4 numbers that form a square on the table) on 1, 2, 4, 5 or first dozen

- The corner bet on 1, 2, 4, 5 or second dozen

- The basket bet (which wins on 0, 00, 1, 2, 3) or red

- The basket bet or black

Text Attribution

This text was adapted from Chapter 7.8 of Contemporary Mathematics, textbooks originally published by OpenStax.